The Lobbyist

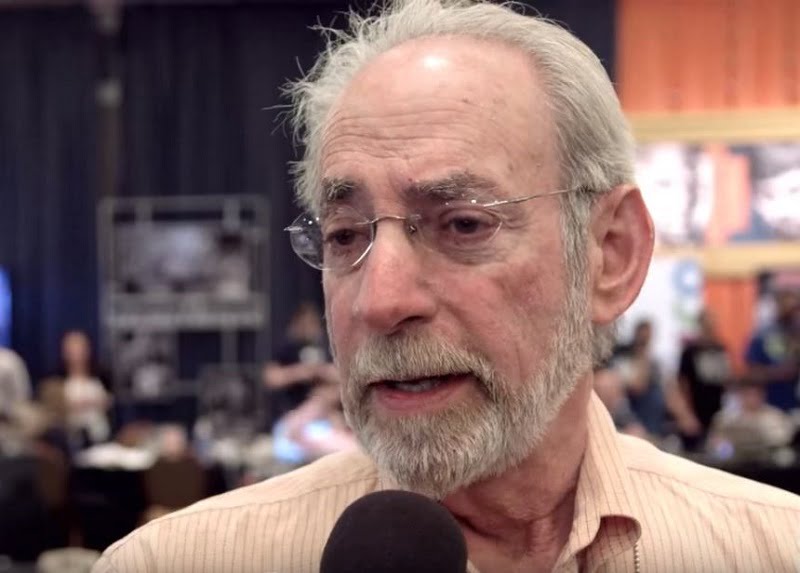

Marc Ratner spent 21 years with the Nevada State Athletic Commission, including 14 as its executive director. In the mid-1990s, when MMA was in its infancy, Ratner spoke out against it, saying that it would never be allowed in Las Vegas. In 2006, however, Ratner accepted a job with the UFC as its vice president of regulatory affairs. “I had the best regulatory job in the world,” said Ratner. “But what intrigued me about the UFC was that it was a brand new sport. I wanted to be on the ground floor, to be a pioneer and try to get it legalized. You can’t do that in basketball or boxing, since those sports have been around so long.”

Ratner has seen the sport make leaps and bounds since its early outlaw days when the UFC was struggling to fill small auditoriums and fighters had to be careful not to strike with closed fists for fear of being arrested for assault. “It’s not 1995 anymore. It’s no longer ‘no-holds-barred,’” Ratner said, pointing to the changes and reforms in the sport over the last decade. “It’s a very regulated sport, and that’s how it should be.”

When Ratner first joined the UFC, MMA was sanctioned in 22 states. The UFC had made Massachusetts and New York a priority when it started its lobbying push, and Ratner has been at the forefront of the effort, while giving the organization a veneer of respectability and legitimacy. In stark contrast to Dana White, the flamboyant and outspoken president of the UFC, Ratner tends to be more soft-spoken and measured with his words. Ratner hopes to get MMA events legalized in all 48 states that have athletic commissions (Alaska and Wyoming are the lone exceptions). His task inched closer to reality last November when Massachusetts became the 42nd state to regulate MMA. A month later, the UFC announced an August 2010 card at the TD Banknorth Center in Boston. Then in February, Wisconsin became the 43rd state to regulate MMA, followed by Alabama in March. For Ratner, that leaves New York as his biggest remaining target. According to Ratner, New York represents the “cherry on top of the dessert,” and he is determined to succeed in the state. By his count, he’s been to Albany “seven or eight times” over the last two years, meeting with state legislators in an effort to get the state’s ban overturned.

Ratner’s argument is threefold. “It’s about education, health, and safety,” he said. To emphasize his point, he frequently refers to a 2006 study by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, which found that injury rates in MMA matches were consistent with other sports where striking was allowed. The study also found that MMA actually had lower knockout rates than boxing, meaning that its fighters may be less susceptible to brain injury.

“As opposed to professional boxing, MMA competitions have a mechanism that enables the participant to stop the competition at any time,” the report said. “The ‘tap out’ is the second most common means of ending a MMA competition.” The report explained that a tap out is achieved when a fighter repeatedly taps his hand, giving up. Furthermore, the report found that unlike boxers, who primarily concentrate on the head, MMA fighters target many different body parts and grapple for submission holds and takedowns. The report also said that MMA fighters get knocked out nearly half as often as boxers.

The Johns Hopkins report is consistent with Ratner’s experience with the Nevada State Athletic Commission. From 2001, when MMA was first sanctioned in Nevada, until 2006, Ratner estimates he oversaw over 900 UFC fights, and the most serious injury he ever saw was when Tim Sylvia broke his arm in a 2004 fight against Frank Mir. “Meanwhile, during my time at the commission, there were seven deaths in boxing in 14 years,” said Ratner.

Ratner concedes that MMA fights are violent and that participants do get injured. However, he also points out that there are procedures in place to protect fighters, as well as strict medical regulations that a promotion must follow in order to put on a fight card, such as having doctors at ringside and ambulances and EMT personnel at the facility. “That’s why we want to go through athletic commissions. We want the rules. We welcome them,” said Ratner.

Ratner’s other major point in favor of legalizing MMA – indeed, the one that seems to have the most traction with New York politicians – is the positive economic impact MMA events would have on the state. He cites an economic impact report by HR&A Advisors to bolster his case for legalizing MMA in New York. The study, which was commissioned by the UFC’s parent company, Zuffa LLC, projected that the UFC would bring in over $5 million in revenue for an event in Buffalo and over $11 million for an event in New York City, as well as approximately $1.3 million in city and state taxes. “The UFC is holding an event in Newark, New Jersey on March 27,” said Ratner several months in advance of the promotion’s “UFC 111” event. “It’s still a couple of months to go, and we’ve already sold about three million dollars worth of tickets. I’ll bet that about half the crowd consists of people from New York. Now, why would the state of New York want that income to go to Jersey?”

Raihan Aretin, a 26 year-old restaurant manager in Manhattan said he plans on going to the Newark event for which he paid $150 for his ticket. “New York is the center for all sports,” said Aretin. “We have the Yankees, the Jets and the Giants. I can’t believe we can’t have MMA.”

Nick Bujduveanu agrees. “It’s like having oil on your property and being told you can’t drill it,” he said. “Madison Square Garden would sell out every time.”

These fans won’t have to wait long if Ratner has his way. Ratner believes that the UFC was on the cusp of victory last year after the MMA bill passed the state assembly’s committee on Tourism, Arts and Sports Development on June 3. However, a leadership coup in the New York State Senate ensured that the bill would languish in legislative limbo, at least until the start of the 2010 legislative session. Ratner is still confident that MMA events will soon be legal in New York. “It’s not a question of if it will pass but when,” he said. Not even a Marist College poll in January showing that more than two-thirds of registered voters in New York believed that MMA should remain illegal can dampen his spirits.

“The best poll is the number of pay-per-view buys, the number of bars in showing our events, and our TV ratings in New York,” said Ratner. “If people in New York don’t want it, then they don’t have to watch it. Why hold the people of New York hostage?”

The idea that New Yorkers should be able to watch what many other states allow resonates with Katherine Fiore. She was one of the few female customers at Hooters watching the “UFC 109” pay-per-view, and is not a fan. “I’m here because of my boyfriend,” said Fiore, a 26 year-old accountant in Mahattan who estimates that she’s seen approximately 10 MMA events on pay-per-view. “It should be legal. If you like it, then it should be up to you to watch it.”