[T]here have been plenty of politicians who, at one time, called the venerated halls of Mudge “home.” In addition to [Richard] Nixon, [John] Mitchell, [Pat] Buchanan, [former NJ Governor Jim] Florio, and [former HUD Secretary Carla] Hills, several other prominent national figures have spent time at Mudge, including ex New York mayor John Lindsay, federal judge and DOJ official Harold Russell (“Ace”) Tyler Jr., former New York State Supreme Court justice William Lawless, former Dick Cheney aide I. Lewis (“Scooter”) Libby, and Manhattan federal district judge Jed Rakoff. More recently, in 2016, Democrat Tim Canova, a former Mudge Rose associate, unsuccessfully ran for US House of Representatives in Florida. Perhaps Mudge’s most prominent politico after Nixon, however, was a New Yorker who spent almost no time at the firm.

In 1967, two twenty-three-year-olds who would go on to bigger and better things would report to Nixon Mudge as summer associates. Peter King, a working-class Irish Catholic from Queens who would become a longtime US Representative from Long Island, was a rising 3L at Notre Dame Law School when he met his future GOP colleague on the first day of orientation: Rudy Giuliani. The future mayor of New York City and unsuccessful presidential candidate was, at first glance, an odd choice for Nixon Mudge. For one thing, the NYU Law student considered himself to be a liberal Democrat in the vein of Bobby Kennedy. In fact, one could argue that, when it came to politics, the proud Italian Catholic Giuliani’s holy Trinity consisted of JFK, RFK, and Teddy. According to a 1997 Daily News profile, Giuliani cried when JFK was assassinated, distributed RFK fliers during Bobby’s victorious 1964 Senate campaign against incumbent Kenneth Keating, and once yelled at his aunt for making a joke about Teddy and Chappaquiddick.

So it was strange to see him working at Nixon’s law firm. To be fair, it’s not like he crossed paths with the future president regularly. The annual summer associates’ lunch with Nixon was one of the only occasions where they would have a chance to meet. And as one of Giuliani’s colleagues pointed out, it’s not like Nixon would have identified the future mayor as a potential political star the way he had with Donald Riegle. “I didn’t view him as having any leadership skills,” said fellow summer associate Fred Lowther to the Daily News. “If you told me Rudy would become mayor, I would’ve laughed. Rudy Giuliani? You got to be kidding.”

But become mayor he did. Giuliani switched to the Republican Party during the Reagan Revolution in 1980 and went onto a storied career as a federal prosecutor, winning convictions in a number of high-profile cases, including the Mafia Commission trials. After an unsuccessful first run for mayor in 1989, he defeated incumbent David Dinkins in 1993. His tenure saw a sharp decrease in crime (although the decline had actually begun under Dinkins) and a large scale urban redevelopment, particularly in Times Square as the sex shops and peep shows of yore were swept away in favor of Virgin Megastores and Hard Rock Cafes. Additionally, Giuliani was mayor of New York City during 9/11 and emerged as a unifying figure in the aftermath of the attack. Dubbed “America’s Mayor,” Giuliani set his sights on the presidency in 2008, emerging as front runner in polls taken in the summer of 2007.

But before that, he proved that he had learned something from Nixon, after all. In 2005, Giuliani joined forces with Texas-based law firm Bracewell & Patterson, signing on as the firm’s new public partner. The firm, which rechristened itself Bracewell & Giuliani, had desperately wanted name recognition and business for its new office in the Big Apple, and if anyone could do that for them, it was Rudy. He knew all the big players in New York City, and many still held him in high regard as a result of his eight-year run as mayor. In return, he got a nice salary (The American Lawyer reported that the firm paid $10 million, up front, for Giuliani and two of his partners to join) and some flexibility (he would be allowed to continue working at Giuliani Partners, the security consulting business he set up in 2002).

Both Giuliani and his new law firm’s managing partner, Patrick Oxford, denied that the alliance was made with an eye toward the 2008 presidential campaign. Instead, the two talked about how it was a mutual love of the law that brought them together, and Giuliani even claimed that he was more concerned about making sure he liked the people at his new firm than anything else. “That would be a pretty silly way to run for President. You don’t join a law firm to run for President,” Giuliani said, ignoring the fact that Nixon had done just that. Oxford agreed, noting that the two had never even spoken about the presidency.

No one bought it. For one thing, Oxford was a well-known political force in Texas. He had played leading roles on campaigns for prominent state Republicans in the state going back more than thirty years, including George H. W. Bush, John Tower, Kay Bailey Hutchison, and John Cornyn. He had also been a major fundraiser and bundler for then-president George W. Bush and counted both the president and his chief adviser, Karl Rove, as good friends. For another, as The American Lawyer pointed out, Giuliani could have had his pick of jobs with well-known, established firms in New York City. Instead, he chose a three-hundred-plus lawyer firm from Texas full of people that he hardly knew or had never met before and was barely known outside of the Lone Star State. Bracewell wasn’t even considered to be the best or biggest firm in Texas. A former partner told The American Lawyer that he was shocked the firm was able to land someone of Giuliani’s stature while another ex-partner figured Rudy had to be getting something big in return for lending his name and prestige to the firm.

Ultimately, Oxford and Giuliani dropped the façade. When Giuliani formed his presidential exploratory committee in 2007, Oxford came aboard as chairman. Giuliani’s war chest quickly filled up, as he raised over $17 million in the first quarter of 2007, with $2.2 million coming from Texas sources—far outpacing his rivals, including eventual nominee senator John McCain. Giuliani’s nascent presidential campaign received donations from a number of Texas-based donors, including billionaire T. Boone Pickens Jr., who gave $500,000 according to the Wall Street Journal; Richard Kinder, CEO of Bracewell client Kinder Morgan, Inc.; and Tom Hicks, owner of the Texas Rangers and the Dallas Stars.

Those halcyon days of 2007 ended up being the high point of Rudy Giuliani’s 2008 presidential campaign. When primary season got underway, Giuliani contested the traditional first three contests in Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina. However, the bulk of his time and resources went into several big state primaries that took place later, such as Florida, California, Illinois, and New York. Whether this was a decision that was forced upon Giuliani based on falling poll numbers, especially in Iowa and New Hampshire, or whether it was part of a concerted strategy to play to Giuliani’s strengths and emphasize his electability in a general election, is debatable.

Either way, it was a stunning decision that had many political analysts scratching their heads. Long gone were the days when a candidate didn’t have to enter a single primary in order to win the nomination (as Nixon had contemplated doing in 1968). In fact, since 1980, it was vital for a candidate to do well or even win one or two of the first three contests in order to have any shot at the nomination. As a result, Giuliani had no momentum heading into the Florida primary and had boxed himself into a situation where he not only had to win in the Sunshine State but also win big. After finishing a disappointing third, Giuliani bowed to the inevitable and withdrew.

In retrospect, it’s clear that winning the GOP nomination was always going to be a Herculean task for the ex-mayor. Given how conservative the Republican Party has become, it’s doubtful that GOP voters would have ever backed a twice-divorced man who had, previously, advocated on behalf of abortion rights, gun control, and gay rights—or at least it was that way in 2008. In fact, some influential social conservatives like James Dobson had stated that they would never support Giuliani under any circumstances.

Giuliani also learned about the drawbacks of being the early front runner— something Nixon had worked, assiduously, to avoid in 1967. By peaking with more than a year before Election Day, voters had plenty of time to get reacquainted with Rudy’s skeletons, including his messy personal life, his controversial reign as mayor, and his mentorship of Bernard Kerik, the disgraced former NYPD chief and unsuccessful nominee as Secretary of Homeland Security who went to prison on tax fraud charges. In a memorable December 2007 interview on NBC’s Meet the Press, Giuliani seemed on the defensive for the entire episode after host Tim Russert asked the former mayor about several of those skeletons. Russert had even devoted an entire segment to Giuliani’s relationship with Kerik, as well as the use of taxpayer money to protect and drive around Giuliani’s then-mistress and future wife, Judith Nathan.

Giuliani also faced tough questions about his law firm. In that same 2007 interview, Russert brought up work that Bracewell & Giuliani had done for the US subsidiary of Citgo, the state-run oil company owned by Venezuela and its controversial leader, Hugo Chavez. “[My] law firm did never represented Hugo Chavez,” Giuliani responded, indignantly. “They represented— wait, wait—they represented an American company, Citgo, in Texas, that employs maybe 100,000 people, 120,000 people, that sells gasoline, needs to comply with the law. They represented them just in Texas, and then they stopped representing them. And they—not a direct representation of Hugo Chavez. That’s a very unfair way to say it.” The firm would cut ties with Citgo, citing legal conflicts, and Oxford reiterated to The American Lawyer that political calculations did not play a role.

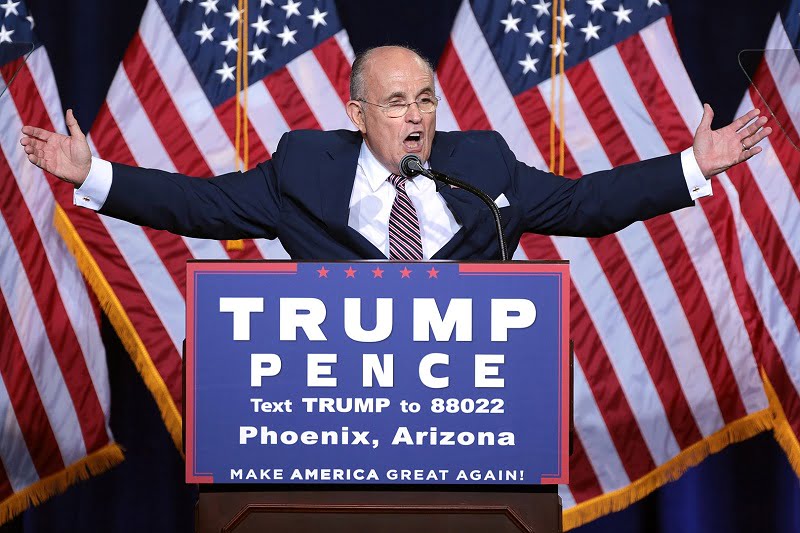

Other law firm clients that came back to bite Giuliani included Yousef Jameel, a Saudi businessman who was sued, along with over two hundred others, by victims of the 9/11 attacks for allegedly funding and supporting Al Qaeda. Jameel’s case was ultimately dismissed, but not before Oxford told Kenneth Caruso, the Bracewell partner handling the case, to get rid of it. “We had a little bit of a misunderstanding with Ken,” Oxford told The American Lawyer. “When I found out about it, I said, ‘Look, buddy, you need to wind this up.’” In the end, the marriage between Giuliani and Bracewell lasted over a decade before the ex-mayor left for a partnership with another Am Law firm, Greenberg Traurig, in 2016. That same year, a twice-divorced man from New York who had, previously, supported abortion rights, gay rights, and gun control would, indeed, win the presidency as a Republican. That man, Donald Trump, had several big-name media supporters and campaign surrogates—however, few of them would defend him with the same type of fervor and devotion as Giuliani.