Donald Trump likes to talk about how he puts his name on everything. Towers. Plazas. Defunct airlines. Mail order steaks. Made in China ties. Even the bottled water in his casinos and restaurants is branded with his name.

Trump’s branding instincts are so ingrained that he even went so far as to chastise George Washington for not naming Mount Vernon, Mount Washington.

“If he was smart, he would’ve put his name on it,” Trump said, according to Politico. “You’ve got to put your name on stuff or no one remembers you.” Apparently, Trump, who currently resides in Washington, D.C. and sleeps a stone’s throw from the Washington Monument, thinks George Washington is about to be written out of the history books because he didn’t think to start selling Washington Axes after cutting down that cherry tree.

Then again, maybe his restraint was because that kind vanity used to be frowned upon.

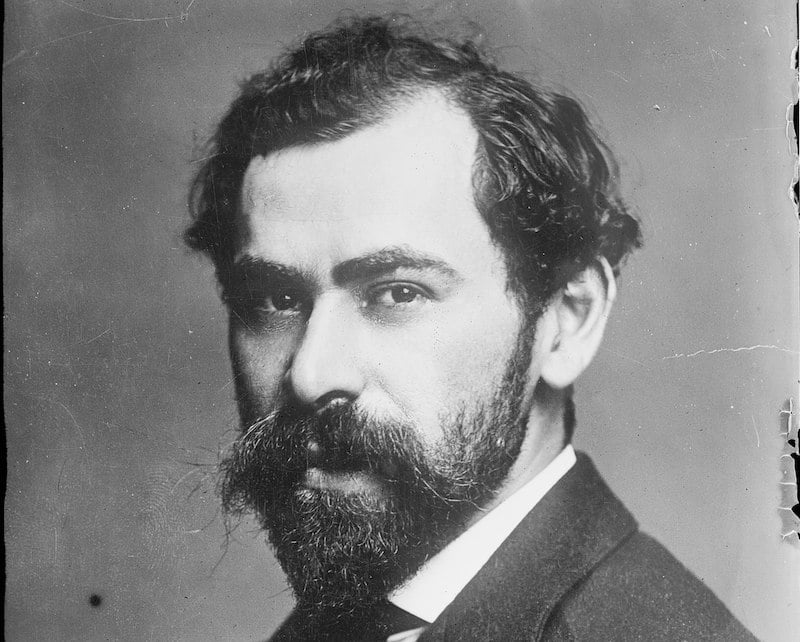

Take Victor David Brenner.

Wanting more artistic coins, President Theodore Roosevelt hired famed sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens in 1905 to redesign four gold coins (the $20 double eagle, the $10 eagle, the $5 half eagle and the $2.50 quarter eagle) as well as the one cent coin. For the double eagle, Saint-Gaudens submitted his famed walking liberty design, which is probably the most beautiful and beloved coin in U.S. history. His Indian-head design for the eagle, though, was much less acclaimed, with some critics pointing out that the image on the obverse resembled that of a Caucasian cosplaying as a Native American rather than the real thing.

It is entirely different from anything ever before issued by the United States Mint, and no patent is needed to protect the designer from infringements. The coin, both obverse and reverse, is a humiliating disappointment, without one redeeming feature, and is a foozle.

Ebenezer Gilbert, numismatist and future author of United States Half Cents (Source: CoinWorld.com)

Saint-Gaudens, who was in poor health at the time, wasn’t able to submit designs for the other coins (although he did design a proposal for a penny, which would have utilized a Liberty head). Roosevelt then turned to Brenner, a Lithuanian immigrant who was an accomplished engraver and sculptor. The president had long idolized Abraham Lincoln, even going so far as to wear a ring during his 1905 inauguration containing strands of Honest Abe’s hair that had been removed during his autopsy, and was keen to associate himself with his predecessor as much as possible. When he saw Brenner’s medal and plaque featuring Lincoln’ bust, Roosevelt thought they would serve as a good basis for the new penny.

While it soon became commonplace, the decision to use an actual historical figure on U.S. currency was unprecedented- even taboo (Indeed, the first time any U.S. historical figure had ever been depicted on a government issued coin had been in 1900, when the Mint released a commemorative dollar coin honoring the Marquis de Lafayette that featured Washington on it). Nevertheless, the U.S. Department of the Treasury reported receiving tremendous popular support for the notion of putting Lincoln on a circulating coin in 1909 as a means of honoring the centennial of his birth. After considering, and ruling out, the half dollar, the Treasury settled on the penny (nine years later, Lincoln would make it to a half dollar – a commemorative half dollar honoring Illinois’s centennial in 1918).

Brenner was now tasked with creating the very first Lincoln cent. Luckily for him, he already had his template. Using the bust he had previously created, Brenner came up with the now-ubiquitous portrait of Lincoln for the obverse. On the reverse, he opted for a simple design of two ears of wheat. Then, as most artists are wont to do, he put his name on his work, placing his initials (“V.D.B.”) at the bottom of the reverse.

Based on the response to those initials, you’d think Brenner had defaced the actual Lincoln Memorial. He wasn’t the first to put his initials on a coin – Saint-Gaudens had put his mark on his highly acclaimed double eagle, albeit in a subtle, non-obvious way. Nevertheless, critics claimed that the presence of Brenner’s initials on the coin was unseemly and exploitative. The Rochester Post-Express opined that “[i]f one designer may put his initial on a coin, and the next one three initials, the next one will want his whole name to appear, and if on coins, why not logically on postage stamps, greenbacks and bonds?” The New Orleans Picayune, meanwhile, went even further, warning ominously that “[i]t may be said to mark the first visible and outward transmogrification of the republic into an empire.” [Both quotes from David W. Lange, The Complete Guide to Lincoln Cents, 2005]

Ultimately, the Treasury Department removed the offending initials, but as Lange points out, the decision was already underway before the public outcry began. The mint halted production on the coin until new ones could be produced without Brenner’s initials on them, but not before 28 million VDB cents were struck in Philadelphia, as well as 484,000 in San Francisco. Brenner, for his part, vehemently protested the removal of his initials. Nevertheless, the numismatist in him recognized that the controversy would be good for his coin in the long run:

The name of an artist on the coin is essential for the student of history as it enables him to trace environments and conditions of the time said coin was produced. Much fume has been made about my initials as a means of advertisement; such is not the case. The very talk of the initials has done more good for numismatics than it could do me personally.

Letter from Brenner to the American Numismatic Association (Source: PCGS)

I recently purchased the above VDB coin. Because mintage was restricted to 28 million (compared to over 72 million non-VDB cents in 1909) these pennies are more valuable than non-VDB cents from that year – yet still affordable enough to collect without breaking the bank.

Of course, that only applies to the regular VDB pennies (which don’t have a mint mark but were made in Philadelphia). Because only 484,000 were struck in San Francisco, the 1909-S VDB is very valuable. Obviously, I would’ve loved to have purchased one of those, but I couldn’t afford it. Maybe one day…