… For every time I wrote about powerful individuals who played outsized roles in numismatic history, I’d have, like, a few nickels. Hey, I’ve only been doing The Coin Blog for a year or so.

We’ve seen how interest groups, U.S. Mint officials, Representatives, Senators (lots and lots and lots of Senators), and even a guy who wanted a paid vacation have willed certain coins into existence.

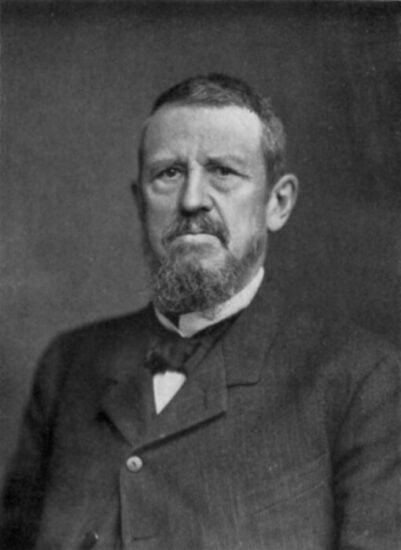

When it came to the creation of the nickel, we have a rich industrialist who had lots of powerful friends in Congress and wasn’t afraid to use his influence.

The U.S. had used nickel in its coins before, but not on a widespread scale. Previously, one-cent coins had consisted of 100% copper and copper wasn’t cheap. As such, the cost of minting a penny was often greater than its face value – something that the Mint continues to wrestle with to this day:

Beginning in 1856 with the Flying Eagle cents, the Mint tried to decrease the cost of minting a penny, including reducing its size and decreasing the copper content, eventually settling on an alloy consisting of 88% copper and 12% nickel.

Sensing a good business opportunity, industrialist Joseph Wharton sold his interests in zinc mining in 1863 in order to invest in nickel mines. Wharton, who would probably be best remembered for founding the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, soon established himself as the largest nickel manufacturer in the country, founding American Nickel Works and buying the Gap Mine in Pennsylvania, a large source of raw material.

Wharton’s business sense may have been acute, but his timing couldn’t have been worse. Turns out, the copper-nickel alloy was too unyielding and damaged the Mint’s dies and presses. Additionally, there wasn’t enough nickel being produced by Wharton’s mines to keep up with the demand for one-cent coins, so the Mint asked Congress to pass a bill to get rid of the alloy in favor of a bronze cent.

Wharton didn’t like that very much, so he spoke to some of his favorite members of Congress and tried to kill the bill. Famed Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, who represented the district where Wharton’s mines were located, took to the House floor on April 20, 1864, and spoke out against the measure.

I know that one gentleman [Wharton], a resident of Philadelphia, has expended some $200,000 in opening a nickel mine and preparing the machinery, which is now in full operation and is able to supply all the nickel wanted in this country. Just at the moment when this business has been stimulated in the way I have mentioned by the government, we are asked to destroy all this property, for nickel is not much used except for hte purpose of coin and to mix with German silver. Shall we destroy all this property because by coining with another metal more money may be saved to the government? I believe it bad policy. If the present nickel cent costs too much, reduce its weight.

Thaddeus Stevens, Speech on floor of House of Representatives, April 20, 1864.

Wharton and Stevens were unable to stop the 1864 Coinage Act from becoming law, which among other things, mandated the use of bronze in one-cent coins. However, the end of the Civil War gave Wharton another opportunity to see his precious nickel turned into U.S. currency. During the war, people had started hoarding silver and gold coins due to the instability and chaos, a trend that continued even after the Confederacy surrendered. This applied even to the smallest denomination of silver coins- the three cent piece. To keep up with demand, the government had issued temporary paper notes to take the place of smaller denominational coins, including three cent pieces. However, these notes, derogatorily referred to as “shinplasters,” were cheaply made and easily deteriorated. Once the war was over, they needed to be replaced with a more permanent solution.

Wharton saw his chance and began pushing his nickel as the answer. He published a memorandum in 1864 arguing that nickel was a superior metal for all small-denomination coins, especially when compared to other metals like aluminum, tin, cobalt, German silver (a copper/nickel/zinc alloy), and in particular, bronze, which he dismissed as “so cheap and easily made, and easily worked a composition, that it offers no difficulties to counterfeiters” in addition to having a “disagreeable odor and a valueless appearance.” Keeping in mind previous criticisms of nickel coins, Wharton argued that its hardness was its best asset, since that meant it would be difficult to counterfeit. To that end, he suggested that all coins under 25 cents should be comprised of a 75-25% copper-nickel alloy.

In a word, I conceive these alloys to possess to a very great and superior degree all the properties desirable in a metal for low coinage, being cheap enough, sightly, convenient, durable and very hard to counterfeit. They can be worked into coins with perfect success by such means as are at the command of our Government, while the skill, the apparatus and even the material are rather beyond the reach of counterfeiters.

Joseph Wharton, “Project for Reorganizing the Small Coinage, of the United States of America, by the Establishment of a System of Coin Tokens, Made of Nickel and Copper Alloy,” 1864.

When it came time to debate the composition of a new three-cent coin, Wharton’s efforts won out and Congress authorized a 75-25% copper-nickel coin in 1865 with very little debate (the bill was passed on the morning of Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration, so it’s probably fair to say these guys had other things on their minds that day).

Buoyed by his victory, Wharton pressed on and started pushing for a nickel five-cent piece. Half-dimes had never circulated well, and like other silver coins, had been subject to excessive hoarding.

Wharton got an unexpected assist from an overzealous Treasury official who wanted to see his face on U.S. currency a bit too much. In 1864, Congress had authorized the printing of additional 3, 5, 10, 15, 25 and 50 cent notes, and had intended the five cent note to bear the portrait of famed explorer William Clark. Unfortunately, they soon learned a lesson in proper legislative drafting as the bill only mentioned “Clark.” Spencer M. Clark, then Superintendent of the National Currency Bureau, saw the bill and the flattered official reasoned that he must be the “Clark” that was being honored by Congress — that or he took advantage of a statutory ambiguity to make his dream of appearing on U.S. currency come true. Either way, Congress was outraged and soon passed a law that no living person could appear U.S. currency (a law that would be broken a few times in the years since).

“It is derogatory to the dignity and the self-respect of the nation,” Rep. Russell Thayer (R-PA) said in response to the new “Clark” notes. “I trust the House will support me in the cry which I raise of Off With Their Heads!”

Clark’s faux pas opened the door for Wharton to get Congress to consider nickel five-cent pieces. Applying the same logic he used to get the nickel three-cent piece passed, Wharton began leaning on his friends in Congress for a bill replacing the silver half-dimes with nickel five-cent pieces. Evidently, his powers of persuasion had only increased, as Congress not only passed the bill without debate in 1866, they even increased the weight of the new nickels, giving Wharton extra reason to smile.

However, that smile would dim slightly once he saw the fruits of his labor. In designing the new nickel five-cent piece, Mint Chief Engraver James Longacre experimented with patterns featuring Washington or the recently assassinated Lincoln before settling on an established design. The ensuing Shield Nickel was patterned after the two-cent piece that was in circulation from 1864–1873. The obverse on the nickel contained a very similar-looking shield, while the reverse also looked like that of the two-cent piece, only with the ears of wheat on the two–cent piece removed in favor of a circle of thirteen stars and rays around a big number “5.”

As predicted, the hardness of the nickel made it difficult to properly strike the coin, and the rays on the reverse would be removed starting in 1867 due to production problems. The rays had also been controversial from a design standpoint, as some believed the stars-and-rays reverse was a bit too similar to the Confederate stars-and-bars. Indeed, not many people had nice things to say about the Shield Nickel’s design. The American Journal of Numismatics called it “the ugliest of all known coins,” while Wharton, himself, called it “awkward and humpy” and “entirely devoid of resonance.” “The design of its face strongly suggests the old fashioned pictures of a tombstone surmounted by a cross and overhung by weeping willows, which suggestion is corroborated by the religious motto,” he added. “It is a curiously ugly device.”

Perhaps that’s why Shield Nickels aren’t highly popular amongst collectors. As such, they remain relatively affordable (with a few exceptions) despite their age and historical significance. Shield Nickels in mint or near-mint state can be hard to find due to the problematic striking process, but if you do find one, it probably won’t cost an arm and a leg. So for completists out there, it’s possible to compile a complete set of Shield Nickels without breaking the bank.

In the intervening years, the nickel has become such an integral part of our system of currency, it’s hard to imagine a time when they weren’t. I guess it pays to have friends in high places.