Sometimes, it takes a while for people to get outraged about a law.

Maybe it’s all of the legalese — for instance, it is not the case that double negatives are unacceptable in drafting legal documents.

Maybe it’s the arcane parliamentary procedure that only C-SPAN junkies have the wherewithal to comprehend or stomach. Heck, even C-SPAN gets bored during quorum calls and starts playing background music.

Or maybe it’s not always apparent what a law’s effects will be until it’s been in effect for a few years.

That was the case with the Coinage Act of 1873 (also known as the Fourth Coinage Act). A few years after its enactment, the law would become known as the “Crime of 1873” and helped spawn a powerful political movement that influenced multiple presidential elections.

But at first, it was a whole lot of nothing.

The Coinage Act had been kicking around for several years and had undergone different iterations before it was finally passed and enacted in 1873.

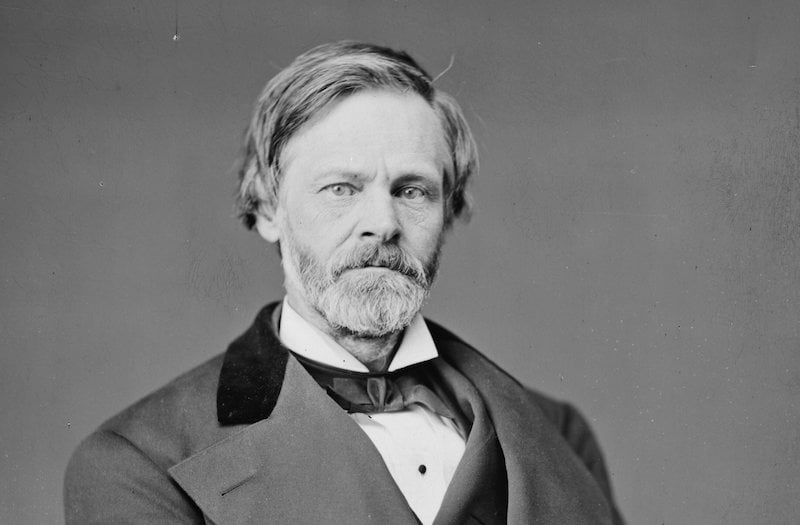

Originally introduced by influential Ohio Senator John Sherman (a/k/a General William T. Sherman’s younger brother who authored the landmark Sherman Antitrust Act), the bill had a lot of stuff in it. To wit:

There was something in there about eliminating the two-cent coin, the silver three cent piece and the half-dime — three denominations that weren’t used much and have been largely forgotten about outside of numismatic circles.

There was something in there about discontinuing the production of silver dollars and no longer allowing customers to bring silver bullion to the U.S. Mint and have them struck into silver coins for free (minus a small charge for production costs).

There had been a proposed thing about using nickel to produce one cent coins that had been inserted at the behest of Joseph Wharton, the influential magnate who loomed large over later coinage battles. Unlike many of the other parts of this bill, that part actually caused some spirited debate on the floor and resulted in the bill being shelved in 1871.

And there was a thing about creating a “commercial dollar” that would be exported to Asia in order to compete with similar coins floating around there.

As a result of that last provision, we got the U.S. Trade Dollar, with the first ones rolling off the belt in 1873. Because the Coinage Act discontinued silver dollars, it was problematic to then authorize the minting of a new silver dollar. As such, the coins would be exported to Asia and would not be circulated in the U.S. The Mint even took the extra step of limiting its use in the U.S., decreeing that the coin would only be legal tender for up to $5.

The Mint solicited numerous proposed designs from various artists and engravers. As you’d imagine, these pattern coins are quite rare and are very expensive on the secondary market.

Perhaps the most famous of these pattern coins is the “Amazonian.” Mint chief engraver William Barber (Charles‘ father) came up with a design featuring Lady Liberty as a sword-wielding warrior on the obverse (interestingly, the word “liberty,” which is usually printed somewhere near her, is not present here — probably because of the war theme).

The design has long been acclaimed as one of the most beautiful coins ever designed and has become highly sought after by rare coin collectors. When I attended the ANA World’s Fair of Money a few years ago, a beautiful Amazonian pattern was displayed alongside other prized rarities like the 1943 copper penny, the George Morgan “schoolgirl” design and the 1907 ultra high-relief Saint-Gaudens double eagle.

However, the Amazonian pattern was ultimately rejected in favor of a less militaristic, more utilitarian image from Barber, which contained an obverse image of Lady Liberty sitting near the ocean, facing left (towards the west and Asia) and holding out an olive branch. The reverse bore the required bald eagle design, as well as a line regarding its silver composition: 420 grains, 900 fine.

The line was meant to let Chinese merchants know how much silver was in each coin (at least, the ones who could read English), putting it roughly on par with its competitors, most notably the Mexican 8-reales coin, the British trade dollar and the French Piastre and giving it more silver than the popular Maria Theresa Thaler. That also differentiated it from the standard U.S. silver dollar, which was lighter and contained slightly less silver (412.5 grains compared to the aforementioned 420 for the trade dollar).

The trade dollar was given the stamp of approval by China’s emperor and it entered the market there.

You must know that the ‘Eagle Trade Dollar’ that has lately come to Hong Kong has been jointly assayed by officers specially appointed for the purpose, and it can be taken in payment of duties, and come into general circulation. You must not look upon it with suspicion. At the same time rogues, sharpers, and the like, are hereby strictly forbidden to fabricate spurious imitations of this new Eagle Dollar, with a view to their own profit. And should they dare to set this prohibition at defiance, and fabricate false coin, they shall, upon discovery, most assuredly be arrested and punished. Let every one obey with trembling! Let there be no disobedience!

Proclamation by the Emperor of China, October 1873

(And it worked because no one in China ever forged a coin again.)

That’s not to say there weren’t problems. The mints in charge of striking the Trade Dollar immediately raised complaints about design flaws. However, according to PCGS, those problems weren’t addressed until late-1874, in part, because the Mint was busy producing the 20-cent piece to mollify Senator John P. Jones of Nevada, a leading proponent of silver coinage and co-owner of a silver mine.

Mint director Henry Linderman proposed a completely new design to commemorate the nation’s centennial in 1876. However, he was informed that such a change would require Congressional approval. Plus, there wasn’t much point to celebrating American independence on a coin designed to circulate in Asia.

Despite its issues, the coin ended up doing reasonably well in China, although it was far more successful in the southern part of the country.

What was not as successful was the plan to keep the coin out of the U.S. The coin inevitably made its way back to American shores, which was now awash in silver thanks to the discovery of the Comstock Lode.

As such, the market for silver tanked, allowing businessmen to buy trade dollars for cheap and then pay their employees with the coins at face value. Those employees then got a rude awakening when they tried to use the coins to buy things and found out that they didn’t have the buying power they should have. Merchants also got hosed when they tried to redeem the trade dollars at banks.

That was emblematic of a much larger struggle going on at the time. Mint officials, as well as pro-gold standard politicians like Sherman, had their reasons for moving away from bimetallism and embracing the gold standard. For one, other powerful countries like England and France were on a gold standard, so standardizing U.S. currency with theirs would make it more stable.

Additionally, gold and silver dollars were created based on a fixed ratio (the famous “16-1” ratio whereby 16 ounces of silver could purchase 1 ounce of gold). However, because the prices of both metals tended to fluctuate based on supply and demand, it was often the case where the ratio was out-of-whack with the market. For instance, at the time of the 1873 Coinage Act, silver prices were fairly high due to Civil War era hoarding. That had the effect of driving down the price of gold, allowing speculators to use silver to buy cheap gold, sell it at a profit overseas and then use the money to either buy more silver. Or they could hoard the gold, knowing its price would, inevitably, go up.

Nevertheless, in the years following the passage of the Coinage Act, miners, farmers and others who were reliant on silver remained blissfully ignorant of the new standard. That changed when, as a result of the Coinage Act and the Comstock Lode, silver prices started falling. When they sought to redeem their cheap silver for coinage, figuring they’d make money as a result of the fixed ratio, they got a rude awakening and to say they were mad was an understatement.

An ensuing economic panic exacerbated the situation and the issue of “free silver” became a socio-political powder keg. Poor people, especially farmers, felt like they had been screwed over by the elites, and economic populism started to catch on. Sympathetic newspapers began pushing the idea that the Coinage Act had been hastily rushed through Congress, and as a result, politicians had been unsure of its consequences.

Some, including Sherman and U.S. Representative William Kelley (R-PA), who had introduced the legislation in the House, were able to read the tea leaves and claimed they had not been trying to demonetize silver. Sherman even went so far as to claim in his autobiography that there was obviously no intent to do so, otherwise they would have gotten rid of all silver coins, not just the silver dollar.

Historians don’t buy this. “Senator John Sherman, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, had been determined to demonetize silver from at least 1867 and had arranged to have a bill to that effect drafted at the end of 1869,” wrote Walter T. K. Nugent in his 1968 book, Money and American Society, 1865–1880. Nugent noted that Sherman, Linderman, Treasury Secretary George Boutwell and Treasury employee John Jay Knox worked together, hand-in-glove, for years to make sure it happened.

Intentional or not, the Coinage Act had changed things and Free Silverites soon took over the Democratic Party with William Jennings Bryan as their standard bearer. They even attracted some Republicans from silver producing states like Jones of Nevada.

They came up short in their ultimate goal of winning the White House, but they did succeed in bringing bimetallism back. The Bland-Allison Act in 1878 allowed for the resumption of silver dollars, albeit by requiring the government to purchase silver for coinage purposes, taking the profit motive away from speculators and miners. The bill was enacted over President Rutherford B. Hayes’ veto, and the Morgan Dollars we all know and love came out later that year.

In a sign of just how much things had changed, Sherman, who had become Treasury Secretary, had actually encouraged Hayes to sign Bland-Allison. In fact, when Sherman returned to the Senate after his time as secretary was up, and he helped shepherd the Sherman Silver Purchase Act in 1890, a bill that built on Bland-Allison by requiring the government to purchase a minimum about or silver every month for coinage purposes.

When it came to the Trade Dollar that he had helped create, Sherman was also responsible for its ultimate demise. The coin was demonetized in 1876 and Sherman, who was still Treasury Secretary at that point, ordered a halt to production in 1877. After a brief respite, he ordered a final halt in 1878. Nine years later, with 7.7 million Trade Dollars still in circulation in the U.S., Congress finally allowed holders to redeem them at banks for their face value.

The issue of this coin was an expensive mistake — its motivation mere greed, its design a triumph of dullness, its domestic circulation and legal-tender status a disastrous provision of law leading only to ghastly abuses, its repudiation a source of hardship for Pennsylvania coal miners and other laborers held in virtual peonage by company stores, its recall a long overdue but very mixed blessing, and its collection a source of decades of frustration.

Walter Breen, quoted in Coin Week, June 12, 2015

These days, U.S. Trade Dollars are highly collectible and sought after. Because they mainly circulated in Asia, they’re not as common in the U.S. and tend to cost more than Morgan or Peace Dollars. Chinese merchants often put chop marks on them to test their authenticity, so finding pristine ones can be difficult (although some collectors like the chop marks since it means it was definitely used in commerce).

And, of course, there are the ultra-rare 1884 and 1885 proofs. Only ten 1884 proofs and five 1885 ones are known to exist and all of them are worth a fortune. One sold in 2021 for $480,000 and another went the previous year for $552,000.

The origin of these coins is shrouded in mystery— PCGS claims they were struck on the down-low by some Mint officials to be sold on the secondary market for a fortune.

Stack’s Bowers, however, casts doubt on the profit motive and claims the coins were probably struck legally, noting that “trade dollars were not popular with numismatists at the time.” Additionally, the coins weren’t discovered until 1908 — surely if someone had struck them surreptitiously, they would have tried to cash in much earlier, right?

And surely, the Mint, which has never been shy about going after people who possess or sell coins that shouldn’t exist, would have cracked down on these Trade Dollars.

So maybe of all the “crimes” associated with the Coinage Act of 1873, those last few proofs weren’t one of them.